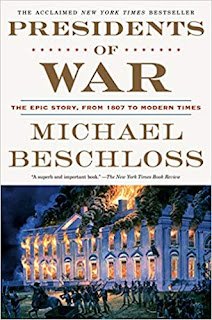

The Presidents of War – by Michael Beschloss

Michael Beschloss is one of my favorite historical authors, and the subject of U.S. Presidents is one of my favorite topics, so I had pretty high expectations for this one. Fortunately, Beschloss didn’t let me down. This was one of the most enjoyable historical accounts that I’ve read for quite some time.

When looking at the tenure of any U.S. President, their legacy seems to be mostly defined by the particular travails the country is experiencing, and the more serious the travails are, the sharper the presidency seems to be defined. Often when a commander in chief serves over a period of time where nothing substantial seems to happen, history seems to mostly forget the individual. I’m guessing most Americans aren’t familiar with names such as Benjamin Harrison or Calvin Coolidge. Other names, though, such as Franklin Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln, seem to be known by all including young children in grade school. Would history remember these two presidents had they not presided over the American Civil War and World War II? I doubt it.

Some of the lesser known wars, though, coincidentally have modern day citizens draw a blank if you were to ask them who the president was, or even what the war itself was about. Names such as James Polk and William McKinley are not on most people’s radar, and the more time slips away, the more inconsequential those names tend to be.

What Beschloss does in this book is give a short history of the country’s 8 major wars (from The War of 1812 through Vietnam) with the main focus being on the commander in chief, and the particulars of the role the man played getting us into the war, and how they navigated the country through the conflict. This is not a very easy task to do. Take FDR and World War II for example. My guess is that there have been hundreds of books written on Roosevelt and thousands written on the second world war, so how can one pick and choose to come up with a concise, yet detailed summation to include here? Fortunately, Beschloss highly succeeds with this task.

He manages to lead of each chapter devoted to the start of each war with a memorable, everyday man anecdote, and then manages to also give a bit of history of each president. We then learn a bit about the particular conflict, and how the president got the country involved, and how the leader carried the country through the entire conflict – good, bad, and ugly. It’s interesting to learn just how little things have actually changed over 200 years when talking about politics. No matter how a war might need U.S. involvement, whichever party is on the opposite side of the political fence always has to grandstand and gripe about everything the president does. The only exception could be the second world war, yet Roosevelt had plenty of adversaries during the first three years of that war before the U.S. was attacked and became involved. There were many who didn’t like many aspects of how Roosevelt navigated the tough waters of neutrality while trying to help cross-continent allies defend themselves against tyrannical dictators, so there was still plenty of political bickering going on.

Then, of course, we must face the ugly fact that not all wars that the country entered had altruistic motives. A particularly harsh example is President James Polk and how the country got involved in the Mexican-American War during the 1840s. The author alleges that Polk was simply greedy and wanted to acquire more land under the U.S. umbrella, so why not take advantage of a neighboring fledging country that seemed to be led in a rather backwards fashion?

Of course, Vietnam is still present in many readers’ memory, so we get to relive that sad part of history again. I also thought that this was the best part of the book. By ‘best’, of course, I mean the detail of Lyndon Johnson’s involvement, not that the war is anything that the U.S. should look back on fondly in any means. Ironically, though, The Korean “Police Action” seems to be represented rather thin here. It could be that there simply wasn’t much “history” to write about, especially President Harry Truman’s involvement. (In many ways, the bulk of that war was mostly a stalemate at the 38th parallel, so there probably weren’t that many details to relive.)

I would highly recommend this book for all, but being the history geek that I am, I would honestly prefer someone with no knowledge to read a separate volume devoted to each of the conflicts, and each of the presidents who presided. If, however, that’s too much for one’s palate, this book serves as a good “Cliffs Notes”. It may even stir the reader’s interest to want more.

Note: The George W. Bush Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts are mentioned in this book’s epilogue and only a brief summary is included. Even though these wars were long, there was relatively little combat, injuries, and (thankfully) death, so this might be why Beschloss decided to basically skip these. Although these wars (particularly Iraq) did shape the Bush 43 presidency, the conflicts seemed to be on the back pages of the newspapers during most of the U.S. involvement, so most remember these wars as an unpleasant undercurrent as opposed to a radical struggle with worldwide consequences.